Menu

MenuBy Vishnupriya Bhandaram I First Post I December 22, 2015

Crime, usually that of rape, sexual violence or violence against a particular gender has a social aspect which tends to get overlooked in most discussions, primarily because as consumers of crime news, it becomes tough to separate emotion from a phenomenon. Juvenile delinquency is not one isolated incident, it is a criminal phenomenon. Over 33,000 juveniles in the age group of 16 to 18 years were arrested in 2011 in India, most of the charges were that of rape and murder, according to Sibnath Deb’s research as discussed in Child Safety, Welfare and Well-being: Issues and Challenges. The number of juvenile delinquents has been on a steady rise, notes the author.

It would be egregiously wrong to think that children cannot murder or rape. For example, take the Steubenville rape case, two 16-year-old footballers were found guilty of raping a drunk teenager. A 12-year-old raped his teacher in Sunderland. A 12-year-old raped two girls in Bolton; he was 11 at the time he committed the crime against the girls aged 10 and 11. In the US, juveniles arrests make up for 20 percent of sex offence crimes. In India, National Crime Record Bureau statistics show that the number of juveniles raping girls and women has shot up in the last three years.

We must take cognisance of the fact that the environment the children are growing up in now is vastly different from a decade ago. We are living in a ‘super sexualised world’ and the access that a common person has to the amount of depraved information available has grown multifold. It is the adversely sexual aspects of popular culture that are problematic. Nisha Susan and Nishita Jha who have written about increasingly common teenage sexual behaviour in an article in Tehelkatitled, Sex, Lies and Homework say that there is a need to examine the subculture that children belong to which is just as “materialistic, exhibitionist” as the adult world.

The horrific rape that took place in Delhi made the country look inwards and into the culture of rape that we are reifying and perpetrating. The nation perhaps took stock because it happened in New Delhi, in a neighbourhood in the city that was not particularly ‘inappropriate’ for a young girl to be in. The rape did not happen at odd hours, the victim was not in ‘inappropriate’ attire either. Everything about the victim and the circumstances were as ‘normal’ as they could be.

Jyoti Singh Pandey was me. Jyoti Singh Pandey was my colleague from work. Jyoti Singh Pandey was my neighbour. Jyoti Singh Pandey was my classmate. Jyoti Singh Pandey was every Indian girl from the middle class “good household”. The collective conscious of the nation awoke because there was nothing to find fault with, no one could blame it on her clothes, no one could say she egged them on, no one could say that she asked for it. God knows, the media and the audience tried. So, Jyoti Singh Pandey did not ask for it and did not deserve what happened to her.

Now, with the impending release of the juvenile convict in the case, we should make an effort to discuss how we treat the children of this country and the legislation and judiciary must introspect the framing of laws and what can be done to reform individuals who have lost their way.

Juvenile deliquency research: polarised data

The juvenile justice ideology and theory lies in gray areas. There's a lot of conflicting data that exists within the field. For example, there are studies which show that the brain does not vastly differ from the age of 6 and there is only a “remodelling and modelling of various processes during adolescence”. Most sex offenders start offending during adolescence. There is evidence that children have a higher tendency to make decisions based on emotion, a stressful situation heightens the risk of the emotion and guides the choices that the child might make. Howard E Barbaree and William L Marshall in The Juvenile Sex Offender note that “cognitive, affective and behavioral repertoire” already established through other interpersonal relationships (parents, siblings) decides the future of how the individual follows through his interpersonal relationships. However, the pool of research is not unanimously in agreement with this. When it comes to why children take to offending, the answers are frayed around the edges, although delinquency could be commonly attributed to social, economic and cultural factors. DeLematar and Friedrich in Human Sexual Developmentelaborate that the formation of a stable gender identity, sexual identities, managing physical and emotional intimacy, establishing a sexual lifestyle and maintaining it are key for a healthy adolescence.

Research is also divided on recidivism numbers, while a few reports claim that the numbers increase, a few claim they decrease. It would not be wrong to conclude that the opinions that help shape decisions of juvenile justice are vastly divided.

India for its children

The Indian Penal code absolves children below seven years of age from taking responsibility of any crime they commit. The Juvenile Justice Act (JJA) exists for a reason: to protect offenders between the ages of seven and 18. A juvenile under the law is a boy or a girl under 18 years old who have committed a criminal offence. The law prohibits capital punishment from being imposed on the juveniles, irrespective of the seriousness of the crime. India is also a signatory in the UN convention on the rights of child which mandates that under 18, a person cannot be tried as an adult.

A Human Rights Watch report says: “Their forming identities make young offenders excellent candidates for rehabilitation — they are far more able than adults to learn new skills, find new values, and re-embark on a better, law-abiding life. Justice is best served when these rehabilitative principles, which are at the core of human rights standards, are at the heart of responses to child sex offending.”

Most studies show that often juveniles are victims of abuse, neglect and get into crimes due to peer pressure.

A report in Open Magazine says that the Delhi rape juvenile convict or the Accused No. 6 dropped out of school in class three because his father’s mental capacity had diminished in an accident on a construction site. His family made Rs 1,000 a month, he escaped the poverty to find a better life in Delhi at the age of 11 and did odd jobs. The juvenile convict’s developing years were spent on the streets. The brutality of the crime does not let us see that the juvenile convict could have very well have been a victim of his own circumstances as well. This is one of the core reasons that the Juvenile Justice Act exists, to keep emotion out of the way.

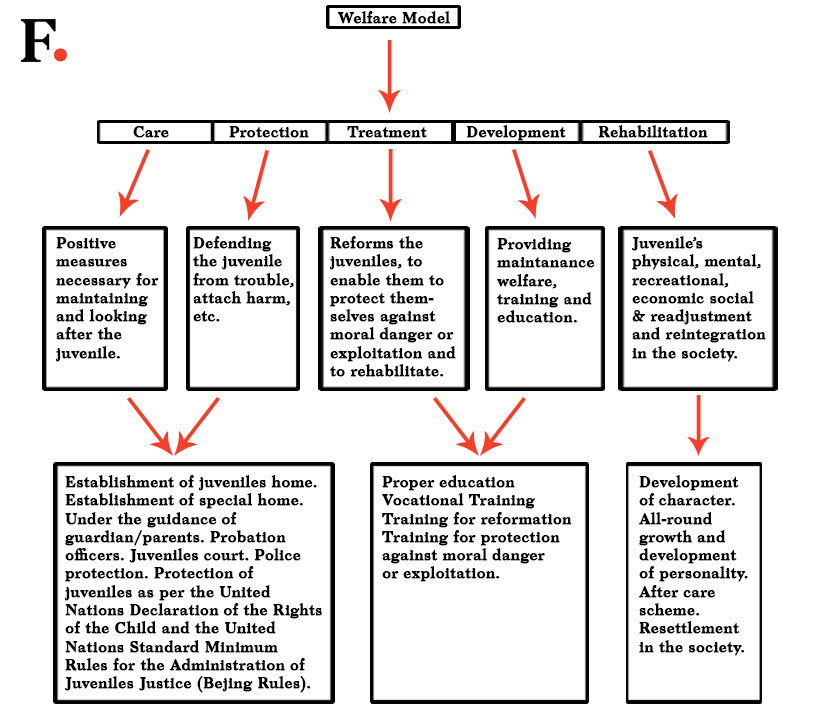

The juvenile justice system, world over, emphasises reform over retribution, rehabilitation over punishment. The Juvenile Justice Act 2000 is in place to help children who are unable to defend their actions or are victims of circumstances themselves. The only questions that remain are: First, whether depravity of an act should be considered during proceedings? Second, what is the punishment that one must provide to someone who has committed a heinous crime, especially by a child? Third, what justice has been done to those who were victims to the crime committed by the juvenile? Fourth, how can the society at large be kept safe from a ‘threat’ such as a juvenile sex offender who committed a severe assault?

Possible solutions

The juvenile justice system has taken the slow route to progress and the system still has to define itself under the care and protection of children generally. The law cannot sway in the direction of the popular opinion wind but the law can be amended to take cognisance of the heinousness of a crime, but that is not enough either.

In the US, sex offenders are registered; this was designed to track sex offenders and make pertinent information available to the public and law enforcement more easily. Currently 38 US states add juveniles to sex offender registries, remaining 12 states only add the names of juveniles convicted in adult courts. This would be the right time to make a call for a similar registry in India for convicted sex offenders (juveniles included), although child’s rights activists decry such registries because it is tantamount to ‘jailing the juveniles through society’. A Human Rights Watch report titled,Raised On The Registry argues that a blind addition of names to registries should not be done without individual assessment of particular needs for treatment or rehabilitation. For juvenile sex offenders being rehabilitated into society, there should be strict parole conditions, mandatory attendance to gender sensitisation programmes.

It is important to understand the heart of the Juvenile Justice Act which believes that children are malleable and with the right treatment and help, the juveniles could become reformed individuals. In the case of the 16 December rape of Jyoti Singh Pandey, the court is and should be duty-bound to uphold the Juvenile Justice Act, as Brinda Karat says inThe Hindu, “certainly there is a strong case for supervision and monitoring of whereabouts,” but she adds that the law cannot be tinkered with.

Any punishment has to have a reparative effect, one that prevents an individual from repeating the crime — this cannot and should not come at the cost of fear, but should stem from a place of understanding in the individual, who takes cognisance of why what he/she had done was wrong, and, therefore, must not do again. If it is not reparative, it is vengeful and the purpose of the law is not to be vengeful.

Yes, India is collectively outraged. Outraged that Jyoti Singh Pandey’s rapist will be let go on Sunday evening. Outraged that the law is failing her. Outraged that this brutal act that occurred means nothing in the eyes of the law. Outraged that our hands are tied. Outraged, just because. But let us outrage about all the other juveniles who should get a chance to reform and repair their lives. Let us outrage over the required amendment and hope that it comes from a place of knowledge and not blood-thirst.