Menu

MenuBharti Ali is the Co-founder & Executive Director of HAQ: Centre for Child Rights, New Delhi

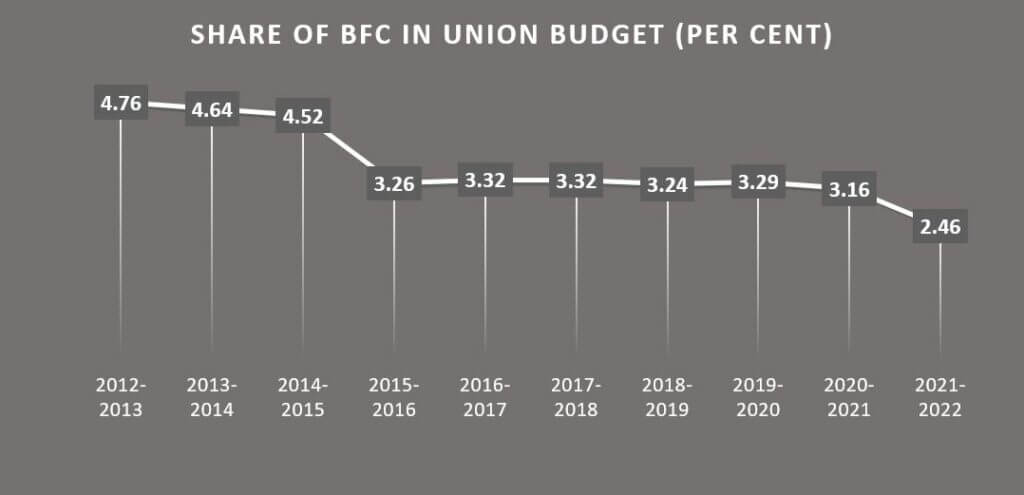

From the time of complete lockdown to the period of partial lockdown through to post- lockdown, children’s rights to survival, development, protection and participation stand severely compromised. The reduced share of children in the Union Budget 2021-22 further points to deprioritizing of child rights. Although the declining Budget for Children (BfC) is not a new phenomenon, it is bound to hit children the most in times when they deserve special attention. The share of the financial allocation for children in this latest budget declined from 3.16% in 2020-21 to 2.46%, the lowest in the last ten years.

Persons below the age of 18 years make up 37% of India’s population.[i] Of these 31% are below the age of 6 years, 53% are aged 6 to 14 years (both inclusive) and the remaining 16% are aged between 15 and 18 years. The COVID-19 pandemic has not spared any age group, though the impact varies in nature and degree across socio-economic classes and in terms of gender and disability.

In a digital India which continues to fall short on child rights related Management Information Systems (MIS) and given the absence of systematic surveys to monitor emergency situations such as the COVID-19 pandemic, much reliance has to be placed on rapid assessments carried out by civil society organisations, anecdotal experiences from the ground and news reports that point to the gravity of the impact of COVID-19 on children and their rights.[ii]

The Right to Life and Personal Liberty under Article 21 is a Constitutional guarantee for all persons, including children. While many other fundamental rights in the Constitution are also guaranteed to children, specific rights pertaining to them are noted in the Constitution’s Directive Principles of State Policy. These are directly related to the Right to Life and thus justiciable in court. Article 39(e) requires the State to ensure that “the health and strength of workers, men and women, and the tender age of children are not abused and that citizens are not forced by economic necessity to enter avocations unsuited to their age or strength.” Article 39 (f) further requires that “children are given opportunities and facilities to develop in a healthy manner and in conditions of freedom and dignity and that childhood and youth are protected against exploitation and against moral and material abandonment.”

The first report of child death during the COVID-19 lockdown was not a COVID-19 related death. It was of a 12-year old girl who had to walk 150 kilometres on foot from Kannaiguda village in Telangana to Bhandarpal village in Bijapur, Karnataka with a group of labourers and died a few kilometres away from her home, possibly due to “electrolyte imbalance and exhaustion” as per the Bijapur Chief Medical and Health Officer.[iii] Some of the immediate measures taken by the central and state governments to take care of children’s survival, health and nutrition needs were evidently not aimed at the likes of this 12-year old, and failing to reach the child labour population or children on the move. Even in the later phases of partial lockdown and post-lockdown, these children have remained out of sight of policy makers.

Children and their Right to Food and Nutrition

According to the India Child Well-being Report 2020 published by World Vision, almost 115 million children are at the risk of malnutrition due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent lockdown.[iv] Another study[v] pointed out that five million children are at risk of falling in the wasting category of malnourishment, while an additional two million children are at risk of being pushed into the severe wasting category due to the pandemic. The study concluded that with “high concentration of children around the undernutrition threshold, any minor shock to nutritional health of the children can have major implications. In the current scenario of national lockdown and restrictions due to coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, it is critical to ensure an uninterrupted supply of nutritious meals and food supplements to the poor children while arresting the infection spread.”

While supplementary nutrition cannot make up for hunger, measures such as extending supplementary nutrition to all children under six years irrespective of their registration in an Aanganwadi centre have not helped. Many needy children remain out of reach as their parents and caregivers remain unaware of such services and no efforts have been put in place for raising public awareness on COVID-19 related programmes for children. Diversion of frontline workers like ASHAs and Aanganwadi workers and school teachers to various other pandemic-related duties has also affected the outreach under the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) programme, Poshan Abhiyan and the Mid-day Meals schemes.[vi]

Although Mid-day Meals are only for school going children, even they have not been able to access the scheme with schools remaining shut since 23 March 2020 when complete lockdown was suddenly announced. Indeed, children do not exist in isolation. If their families received free ration supplies, they too would have got their share, however little that may be. This leads to two questions: did all families without a ration card actually receive free ration? And, whether the ration supplies were adequate for survival and to increase immunity to fight COVID-19? As has been well documented, the answer to both these questions is negative. Not all families without a ration card could access the e-coupons for procuring free ration as was announced in some states like the National Capital Territory (NCT) of Delhi. For those who were able to, the e-coupons fetched very small quantities of ration once or twice at most during the entire period of lockdown.[vii] Many persons found it of no use as they did not have something as basic as cooking oil and spices.[viii]

In its order dated 27 March 2020, the Supreme Court of India in a suo motu Writ Petition (In Re: Regarding Closure of Mid-Day Meal Scheme) expressed concern over large-scale malnourishment resulting from non-supply of nutritional food to children as well as lactating and nursing mothers with the schools and Aanganwadis shutting down during the lockdown. It called upon state governments to ensure that such schemes are not adversely affected.[ix]

Three meals a day is a luxury for many in the country. In the current scenario of the pandemic, where the poor have become poorer due to loss of jobs and livelihood opportunities, supplemental nutrition programmes are unable to cater to all poor children, and loss in dietary intake and dietary diversity is bound to impact nutrition goals. Unfortunately, instead of increasing investments in the Poshan Abhiyan and ICDS, we find a decline in the allocations in Union Budget 2021-22. In the 2020-21 budget, Poshan Abhiyan had received INR 3400 crore and ICDS had received INR 19916.41 crore. The 2021-22 budget has merged Aanganwadis and Poshan Abhiyan under what is termed as ‘Saksham Aanganwadis & Poshan 2.0’ with a much-reduced allocation of only INR 19412 crore, which is less than the allocation for ICDS alone in 2020-21.[x]

Right to Education

In 2002, Article 21A was inserted in the Constitution to guarantee free and compulsory education to all children in the 6 to 14 years’ age group. It took nearly seven years to get a law in 2009 to make this constitutional guarantee implementable. Despite delays and shifting goal posts, substantial headway was made, at least in terms of school enrolment with drop-out rates also witnessing a decline over the years. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has pushed many children out of school at all levels of education. A rapid needs assessment carried out by Save the Children between 7-30 June 2020 revealed that in about 62% of 7,235 families/ households surveyed across 15 states, children had discontinued their education.[xi] According to a UNICEF report released in August 2020,[xii] with closure of over 1.5 million schools In India due to the pandemic, education of 286 million children from pre-primary to secondary levels stands affected, of whom 49% are reported to be girls. The report further suggests that while several initiatives are taken by Government of India to make education available through digital and non-digital mode such as the online Diksha Portal, Doordarshan and TV channels like Swayam Prabha and the National Repository of Open Education Resources, access to remote learning has been skewed. Children from poor families cannot afford a smartphone or computers with an internet connection. Besides, availability of electricity and internet at all times is a challenge. The UNICEF report indicates that the situation is probably far worse as “even when children have the technology and tools at home, they may not be able to learn remotely through those platforms due to competing factors in the home including pressure to do chores, being forced to work, a poor environment for learning and lack of support in using the online or broadcast curriculum.”[xiii]

The gender divide in online education and remote learning is reported by many civil society organisations. With scarce resources, girls find it harder to get access gadgets for online education as compared to their brothers. Moreover, there are many household pressures that invariably fall on girls than on boys. More girls than boys are reported to have committed suicide due to failure to cope with online education and anxieties surrounding the possibility to continue with their education.

Meanwhile, even as the Government of India released the New Education Policy, introducing new and innovative ideas for improving learning achievement levels, it failed to back the policy with adequate financial resources. The 2021-22 Union Budget is bereft of funds required for meeting children’s educational needs, particularly in the wake of the pandemic and its aftereffects. Great risks to children and the public at large are envisaged if educational institutions are opened up.[xiv] Yet, instead of making provisions for children to continue with online education, the share of budget for school education has gone down from 2.18% in 2020-21 to 1.74% in the 2021-22.[xv]

Right against Exploitation

Child labour has been another fall out of the pandemic. As per the 2011 census, India has a child and adolescent workforce of 33 million, of whom 22.87 million are adolescent labourers and 10.11 million are child labourers in the 5 to 14 years’ age group. While older children have had to bear the burden of COVID-19 induced poverty and loss of employment for adults, younger ones too have had to drop-out from education if not more.

Article 24 of the Constitution states that “No child below the age of fourteen years shall be employed to work in any factory or mine or engaged in any other hazardous employment.” The Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act was amended in 2016 to bring it in conformity with the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act, 2009. Employment of children under 14 years now stands completely prohibited so that children can attend school. Although the amended law allows children to help in family enterprises that are not hazardous, it cannot be at the cost of their education. Unfortunately, the pandemic has made both these laws redundant and efforts to make them implementable in such difficult times remain sparse or invisible. Several state governments (Gujarat, Punjab, Himachal Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha and Assam) made relaxations in their labour laws such as increasing the working hours from 8 to 12 hours per day, limiting the time for rest, allowing relaxations in inspections and monitoring by authorities, restricting grievance redress mechanisms, etc. [xvi]A fall in the capacity of employers to pay decent or minimum wages combined with lack of adequate support from the government for small and medium enterprises and industries and a declining economy are bound to raise the demand for cheap labour that is best found in children and adolescents. Article23 prohibits human trafficking, begar and other similar forms of forced labour and states that “any contravention of this provision shall be an offence punishable in accordance with law.” Will these state governments be booked for abetting such forms of exploitation, especially of children?

The rescue of over 70 children from Bihar headed to a sweatshop in Rajasthan was reported in October 2020. The story highlighted the increase in child labour and child trafficking as traffickers found it beneficial to exploit the poor economic condition of people since the outbreak of COVID-19.[xvii] According to Bachpan Bachao Andolan, “between April and September, 1,127 children suspected of being trafficked were rescued across India and 86 alleged traffickers were arrested.”[xviii] Another news report in August 2020 highlighted the case of a 15-year-old girl from West Bengal who went missing after befriending an unknown person on Facebook, pointing to traffickers exploiting increased online availability of children during the pandemic.[xix]

Daughters of India are doomed in every manner. There have been reports of increase in child marriages as parents faced difficulties in coping with the demands of online education and found it more viable to get their daughters married at a low cost during the pandemic. A report by Save the Children, “Global Girlhood 2020: how Covid-19 is putting progress in peril” predicted 12.5 million girls being pushed into child marriages globally in 2020 with an increase of 200,000 child marriages in South Asia, thus “reversing more than two decades of progress that had begun to push the practice into decline globally.”[xx] The COVID-19 situation has multiplied the need to invest in measures that can ensure that girls are able to continue their education and pursue their dreams, measures that secure people’s livelihoods and sources of income and measures that put a check on child trafficking in the name of marriage. Meanwhile, a Task Force set up by the Niti Aayog to examine issues pertaining to the age of motherhood has recommended increase in the age of marriage for girls from 18 to 21 years.[xxi] Even with the best of intentions, such a move implies increased criminalization of the poor for reasons that can be managed through necessary yet focused interventions. Such a recommendation amidst reports of increase in child marriages due to the pandemic is ironical and reflects little concern for the poor. Up until now, conditional cash transfer schemes have helped in delaying marriage of girls till they complete 18 years of age. Even as one wonders if these schemes will have the same effect when the age of marriage is raised to 21 years, it will be important to get data on how many girls married underage since the pandemic stand deprived of benefits under these schemes.

Save the Children’s report also indicates increase in under-18 pregnancies and childbirth risks during the pandemic that are “the leading cause of death among 15 to 19 year olds.”[xxii] During the complete lockdown phase, the author personally experienced three cases where under-age pregnant girls needed emergency medical care and assistance for delivery or abortion. The fear of law held them back from seeking assistance. Raising the age of sexual consent to 18 years and making consummation of a child marriage a sexual offence under the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act 2012 has rendered many young girls in consensual relationship or marriage more vulnerable, deprived of the very protection these laws ought to have provided. The lockdown only added to their woes. In two cases, the husbands/partners had lost their job during the pandemic. In one such case the man had left the girl to fend for herself, while in the other, where the girl was six months’ pregnant, the man refused to take responsibility of the girl or the child to be born. Throughout the six months she had never visited a doctor until she decided to abort the foetus. She went to a government hospital, which refused to admit her as it was focusing on COVID-19 patients. A doctor running a private clinic charged INR 12,000 to give her some medicine and asked her to come the next day. The medicine induced labour and the girl was brought to the doctor in severe pain by a relative. The doctor asked for another INR 15,000, which they could not afford, having exhausted all possible resources. Finally, the matter came to the knowledge of a local NGO engaged in ration distribution, which put out a request for assistance. After more than 30 hours of labour pains, the girl was taken to another clinic where she delivered a stillborn baby. Given her condition, her life too was at risk. Indeed, these three girls have not been the only ones suffering the brunt of the pandemic combined with laws that punish them for exercising their choice and policies that fail to recognize their agency.

Rights of Children Deprived of Liberty

Much to the credit of the Supreme Court of India, one of the earliest COVID-19 related concerns it took cognizance of after the announcement of complete lockdown related to the safety and protection of children in child care institutions and other forms of care under the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act 2015 (JJ Act). The court issued guidelines in this regard in a suo moto Writ Petition, In Re: Contagion of COVID-19 virus in Children Protection Homes, asking Juvenile Justice Committees of the High Courts to monitor the implementation of these guidelines. Interestingly, while the Supreme Court was trying to decongest prisons and child care institutions in order to avoid the spread of COVID-19, the police was picking up young men and detaining them for their alleged involvement in the CAA-NRC protests or the 2020 Delhi riots.[xxiii] Implementation of the guidelines remained a concern for some time. For example, even when the JJBs) passed orders to release children on bail, there was no clarity as to how the children would reach their homes amidst lockdown. In Delhi, the Juvenile Justice Committee of the Delhi High Court held meetings with various stakeholders to deal with some of the challenges faced. Accordingly, the state government was asked to direct the concerned authorities “to treat the bail order passed by the JJB as a permission/pass for the purpose of movement of the child and the person(s) accompanying her/him.”[xxiv] The state government further committed to making some transport available to the child care institutions (CCIs)“at all times for facilitating the movement of the children in reaching their homes as and when bail is granted or for the purpose of their movement to the hospitals in case of any such eventuality.”[xxv]

The lockdown put many families in economic distress. In these circumstances, restoring or releasing children without assessing the family’s capacity could render them more vulnerable to neglect and abuse. Gujarat was the first state to provide monetary allowance to children who were being restored. The Delhi Department of Women and Child Development also issued an order to disburse INR 1500 in cash to a child’s parents along with some dry ration at the time of restoration. JJBs were asked to consider bail applications filed by the Superintendents of the CCIs since their parents/guardians could not have done so in the lockdown, and to relax the rigour of the bail conditions where possible. Arrangements were made to quarantine children in CCIs and set up isolation rooms for newly admitted children. Some other states followed suit to put similar measures in place.

Increased pendency in JJBs, CWCs and Children’s Courts

The one thing that no institution could ensure was expediting trials in cases of children and inquiries pending before JJBs and Child Welfare Committees (CWCs). Since these judicial institutions were not functioning physically for a very long time, the pendency of cases increased, trials and inquiries have been delayed and the caseload has multiplied manifold. In Delhi, for many cases under the POCSO Act, support persons assigned by the CWCs are unable to locate children and their families as they have gone back to their villages during the lockdown.[xxvi] This would be true of most metropolitan cities.

As justice delayed is justice denied, some measures will have to be put in place to expedite the hearings in the coming months. For instance, at least the JJBs should use section 14 (4) of the JJ Act to terminate proceedings in petty offences that have been pending for more than six months.

Other concerns

Mental health care did receive sudden attention from various quarters as reports of domestic violence against children and anxieties relating to Board exams and online education came to be reported during the complete lockdown. Much of the assistance came in the form of online counselling, which could help in a limited way as children found it difficult to open up and share their problems in the presence of family members. The Childline service too struggled to provide timely assistance to children in distress as their frontline workers needed passes and vehicles for barrier free movement, which resulted in loss of valuable time. The irony lies in the fact that Childline had to tie-up with Uber for support of vehicles that had movement passes. The state should have come forward to declare Childline an essential service, which would resolved the problem. With the lockdown being eased out in phases, online counselling and other mental health services that engaged children in useful activities while at home have closed down. Many call it acceptance of the new normal, though nothing is normal in children’s lives.

Of every INR 100 in the central government’s kitty, child protection received the highest share of 7 paise in the year 2019-20, which has fallen to just 3 paise in the 2021-22 Union Budget. The fate of children in such a situation speaks for itself.

To conclude, it is imperative to ask if a nation state that is essentially a welfare state, can chose to ignore the constitutional guarantees during a global pandemic or a national emergency such as the one caused by COVID-19? Should COVID-19 not become an opportunity instead for additional focus on the rights of vulnerable sections of society such as children, particularly those belonging to socio-economically marginalised communities?

The Government of India ratified the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1992 and has been periodically reporting to the Committee on the Rights of the Child on the implementation of the Convention. The combined fifth and sixth periodic reports to the Committee were due as on 15 July 2020. Since the report is already delayed, the Committee will expect the Government of India to also report on the measures taken for upholding and protecting children’s rights during the pandemic. This is the right time to revisit the situation of children since the outbreak of the pandemic and take necessary steps to check child rights violations, restore childhoods and maintain the progress achieved on child rights over the years. Some immediate actions to be considered include:

– Ensuring home delivery of supplementary nutrition and mid-day meals to all children

– Provision of tablets to all children enrolled in schools

– Provisioning of free Wi-Fi and internet services in rural areas

– Setting up village, block and district level child protection committees as provided under the Integrated Child Protection Scheme (ICPS)

– Declaring Childline as an Emergency Service

– Setting up a full-fledged sponsorship programme to cover children who are at risk so that they are not forced into labour or marriage or other exploitative situations or delinquency for that matter. Such a programme must be extended to children who have been restored or released from CCIs so that they find support to survive and continue with their education or vocational training

– Setting up helplines across the country for online counselling of children in distress

– Investing in teacher training on innovative methods of online teaching and evaluation of students

– Strengthening legal aid services for children who come in contact with the law to ensure that –

a) children are adequately represented in matters involving deprivation of liberty so as to ensure that it is for the shortest period of time and only a measure of last resort,

b) they receive a fair hearing and their right to be heard is not compromised under the pretext of an emergency or national crisis,

c) children are able to access victim compensation and witness protection when in need, and

d) delays in the justice delivery process be reduced.

In all efforts, special attention must be paid to the needs of children with disability, children living in areas affected by armed conflict, children in areas affected by natural disasters, children of sex workers, children of single parents, stateless children, unaccompanied minors and children on the move.

Governments should consciously refrain from spending time on amending laws that only bring about cosmetic changes, while children continue to face greater vulnerabilities. This is the time to invest in implementing existing laws, policies, programmes and schemes with greater rigour and zeal in order to reach the last child.

Source: https://covid-19-constitution.in