Menu

MenuDelays due to judicial process of child adoption in India is blamed for making children and parents “wait unnecessarily”, but due diligence is better for their safety and happiness.

Delays due to judicial process of child adoption in India is blamed for making children and parents “wait unnecessarily”, but due diligence is better for their safety and happiness.

It is time for an exposé on child adoption in India, and to do some soul searching so as to become accountable to the children whose lives hang in balance.

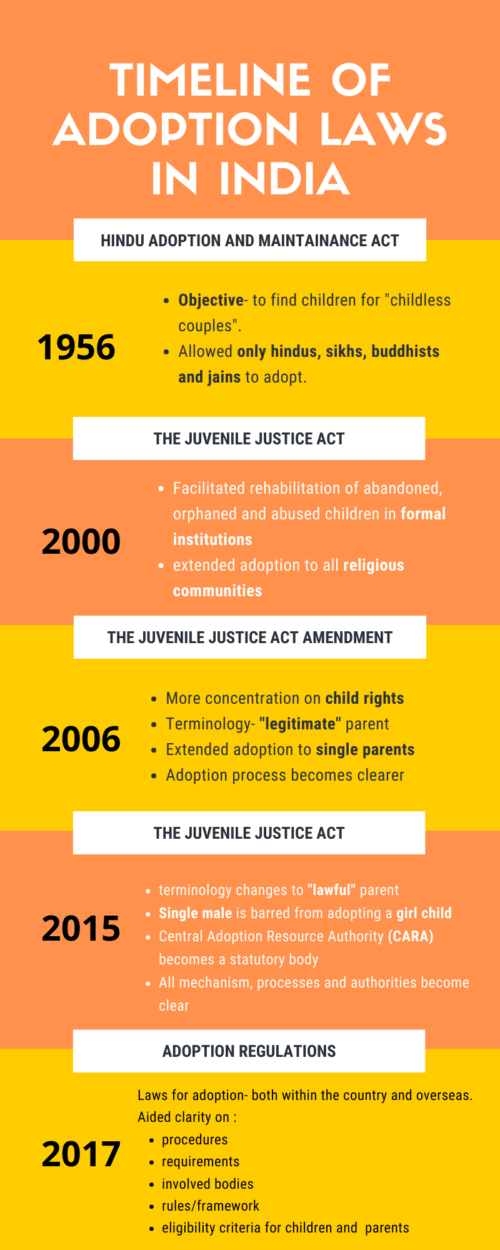

Over the years child adoption in India has received great attention and social acceptance, along with a stronger legal framework to protect the rights of children who are given in adoption, and also to put a check on informal adoptions.

New move to hasten process of child adoption in India has pitfalls

Recently, the National Commission for Protection of Child Rights (NCPCR) asked District Magistrates in 8 identified states to either remove children from the registered child care institutions and restore them to their parents, or place them in adoption or foster care within 100 days.

This step will certainly hasten the adoption process and reduce the waiting period for prospective adoptive parents, but how beneficial is it to the children?

As if this is not enough, in order to expedite the adoption process, the government now wants to eliminate the role of judiciary in adoption and authorise the District Magistrates to finalise adoptions. From identifying and procuring children, to placing them in adoption, there is now a rush to the finish line.

In a rapidly changing social and economic mileu, more and more children are found to be in need of care and protection, requiring a safe and secure family environment. At the same time adoption has become commercialised with a robust market for children, resulting in the need for stronger monitoring mechanisms from time to time, and streamlining the adoption procedures, particularly inter-country adoptions.

A timeline of laws and regulations for child adoption in India

However, a lot of legal reform in the last two decades has been a result of non-implementation or failure of the government to implement existing measures, leading to replacement of one set of measures with another.

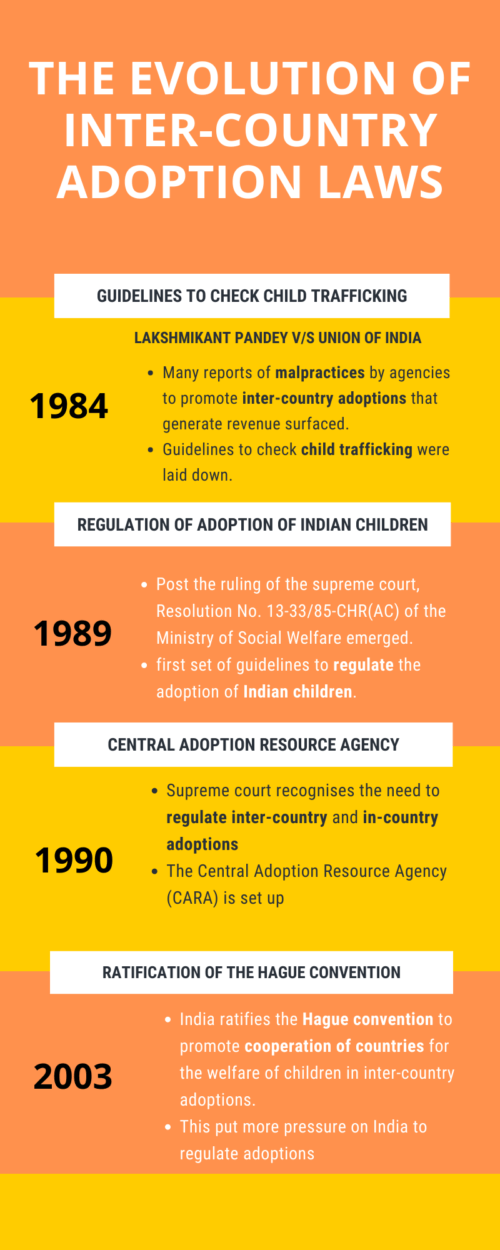

Evolution of the legal framework governing inter-country adoptions

There is a lot of focus on the legal reform carried out in the name of promoting best interests of children, de-institutionalisation, finding alternative family based care for children in the juvenile justice system, and checking illegal practices of child adoption in India.

But while this is being done, we also need to provide families with the appropriate support required to look after their biological children, and protect them in case the family breaks up for any reason, leading to a loss of a social security net. We cannot let this remain ignored or unattended.

The ‘adoption market’ issue

Moreover, many of the changes introduced in the laws for child adoption in India seem contradictory, and are a cause for chaos and confusion.

While ‘informal adoptions’ came to be recognised as ‘illegal adoptions’, a lot of what is now a legal adoption process has illegal elements and unethical practices attached to it.

According to the data presented in response to a question raised in the Lok Sabha, as on 24th June 2019, there were 6971 ‘orphaned’, ‘abandoned’, and ‘surrendered’ children in the 488 Specialised Adoption Agencies (SAAs) in India, and 1706 in the child care institutions that are linked to the SAAs. Not many are interested in finding out who these children are and how do they reach these institutions.

The amendments that brought adoption into the JJ Act also introduced a mechanism for bringing more and more children into the adoption process, inadvertently resulting in a legally sanctified process for getting more children into the ‘adoption market’, for both domestic and inter-country adoptions.

The role of Child Welfare Committees

Child Welfare Committees (CWCs) have been established under the JJ Act in every district with the powers of a Judicial Magistrate of First Class to inquire into and provide for the care, protection and rehabilitation of “children in need of care and protection”.

Such “children in need of care and protection” who are ‘orphaned’, ‘abandoned’ or ‘surrendered” have to be declared legally free for adoption after due inquiry, in order to find them a loving and caring family environment instead of keeping them in institutional care. The JJ Act of 2015 as well as the Adoption Regulations of 2017 require the Child Welfare Committees to report to the State Adoption Resource Agency on how many children have been declared legally free for adoption.

This is unprecedented, as a judicial body is asked to report to a state agency, and is put under pressure to declare more and more children legally free for adoption in India.

The well intentioned cradle baby scheme & its pitfalls

The traditional definition of ‘orphan’ has given way to a new understanding that includes semi-orphans (children of single parents), and allows both unwillingness and lack of capacity of parent(s) to look after their child as sufficient conditions to declare a child an orphan, thus allowing scope for bringing more children into the adoption pool.

Another interesting development has been the introduction of the term ‘surrendered’ children in the JJ Act. In 2007, the UPA government had launched a cradle baby scheme that allows parents to leave their unwanted child in the cradles set up in adoption agencies without running the risk of being identified.

Such a scheme was first introduced in Tamil Nadu in 1991, with the hope that girl children were not aborted, or killed soon after birth, or dumped in some garbage or unsafe place, and their families can instead avail of the option to give them up for adoption.

This scheme clashed with section 317 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) that makes abandonment of children below the age of 12 years a punishable offence, drawing a lot of criticism, so the subsequent NDA government amended the JJ Act in 2000 to give a legal backing to the scheme.

A new concept of ‘surrendered’ children was thus introduced in the JJ Act of 2000. Once a surrender deed is signed and executed before the CWC, it is irrevocable.

To protect these parents who surrendered their children, the 2015 amendment to the JJ Act has gone a step further, by stating that

~ no FIR shall be registered under any law against a biological parent in the process of inquiry relating to an abandoned or surrendered child,

~ and that no penal action shall be taken under the JJ Act against biological parents who abandon their children.

Children born to underage, unwed mothers

This legal provision of surrendering one’s child is being used to ‘procure’ children born to minor unwed mothers and rape victims for adoption.

The Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act (POCSO Act) makes sexual activity with a minor a statutory offence irrespective of consent. It also makes reporting of any sexual activity with a minor mandatory, and non-reporting a punishable offence.

Due to this, many unwed minor girls delivering babies come in contact with the law when they come for pregnancy check ups or at delivery, as hospitals and nursing homes do not want to take the risk of being booked for non-reporting of a statutory offence. The 2000 Amendment makes it safer for these young mothers, so that they can be counseled and can surrender their babies legally.

Ironically, this had been happening earlier too, though illegally. Many adoption agencies that were derecognised and closed down for engaging in illegal practices of procuring children for adoption in India were doing exactly the same. They would run shelters for women and children simultaneously, or alternatively they would tie up with shelters for women, support the women in distress in their delivery, promising confidentiality, and then use their vulnerable situation to counsel them to give up their child for the child’s better future.

So what was seen and acted upon as an illegal practice today stands legalised in the name of promoting and ensuring ‘legal adoption’, but the checks do make things safer.

The question of adoption of older children

The adoption pool is further expanded by allowing adoption of older children who are ‘orphaned’, ‘abandoned’ or ‘surrendered’. However, adoption of older children is replete with complexities, often resulting from adjustment issues between children and the adoptive parents. These children were returned by their ‘parents’ to the institutions.

This is what resulted in the Adoption Regulations providing for what is termed ‘disruptions in adoption’, which can be avoided if due care and caution is exercised before placing older children in adoption, instead of trying to expedite it every which way.

Section 59 of the JJ Act, 2015 provides for giving preference to older children and children with special needs for inter-country adoption.

Invariably the adoption agencies present a very rosy picture about how inter-country adoption can fetch them a better life, with all comforts and luxuries that they will not find in India. The young impressionable minds are unable to comprehend the emotional toll it could take due to a complete cultural change.

Besides, over time, their quest for knowing and meeting their biological parents becomes stronger, while at the same time they may not be able to find adequate support for their search for their roots. This aggravates their stress and anxiety.

Disruptions in inter-country adoption are bound to multiply a child’s trauma and subject the child to all manner of legal procedures in an unknown country. Often such children are not wanted back home. Moreover, they no longer belong to India, having acquired a new legal identity and citizenship. Unable to return, they end up in the child protection systems in the receiving country.

How is this different from foster care?

One may ask that if disruptions have to be allowed in adoption, how is it any different from foster care?

The experience with foster care in countries that have been using it as a form of alternative care also shows — that when children and foster families are unable to adjust with each other, it is the children who get shuffled from one from one foster family to another or one form of care to another.

Section 2(2) of JJ Act, 2015 defines adoption as “the process through which the adopted child is permanently separated from his biological parents…”.

Given that legal adoption everywhere in the world is meant to be irrevocable, and is supposed to bring permanency in a child’s life, is such experimentation with children’s life justifiable? Even if the number of disruptions are fewer compared to those who find loving and caring families, are we as a nation going to allow replacement of caution with haste in finalising adoptions or should we rather engage in processes that reduce the possibility of disruption and allow for thorough scrutiny in every child’s case?

Children with disabilities, and adoption

The state seems to have given up on its responsibility towards children with disabilities, and there has been an emphasis on expediting inter-country adoption for children with disability on the grounds that they have no takers in the domestic scenario.

The state has failed to take care of the medical, educational and rehabilitation needs of children with disability and has instead chosen to convert their situation into an opportunity to bring them into the adoption market. Even children with simple correctible disabilities are passed off from one set of parents to another, who may have the financial ability to invest in the medical procedure required for such correction and rehabilitation.

There is also disregard for the needs of children with disability. Regulation 5 (8) of the Adoption Regulations does not allow adoption by couples having three or more children but creates an exception in this regard for children with special needs, pointing to some kind of a rush to get rid of them.

This is sheer abdication of state responsibility towards children with disabilities.

Horrifying stories of illegal inter-country adoption rackets

Stories of children given in inter-country adoption and their biological parents are also horrifying.

In February 2013, when the Ministry of Women and Child Development was holding an International Conference on Adoption at The Ashoka Convention Centre, a bunch of parents who had lost their children to inter-country adoption were trying to reach the government for help. They just wanted to meet their children who had been traced to different parts of the world with the help of some NGOs.

These parents had filed a missing child complaint or a kidnapping complaint with the police and had been tirelessly following up on their complaints. They were unaware that somewhere in some part of the country, their children had been sold to adoption agencies and were being exported to different countries in the name of inter-country adoption.

Inter-country adoptions cannot take place without necessary paper work and necessary procedures. Yet nobody in the system could find out that these children had biological parents who loved them and were searching for them.

On the contrary, Section 38 of the JJ Act, 2015 allows children to be declared legally free for adoption within two to four months of their production before the CWC. In the case of abandoned children, if the police is unable to trace their biological parents and submit a non-traceabilty report within two or four months, Regulation 6 (11) of the Adoption Regulations, 2017 allows such report to be deemed to have been submitted and proceed further with the adoption process.

Rush to finish the process of child adoption in India dangerous?

From procuring children to placing them in adoption, there is a rush to the finish line.

Referring back to what was said at the beginning, delay in the judicial process is being blamed for making children wait and languish in institutions. For some reason the government thinks that a District Magistrate who is already overburdened with a myriad administrative tasks will have sufficient time to examine all documents and conduct necessary inquiry into every case of child adoption in India before finalizing the adoption.

The District Magistrates are likely to either keep the adoption matters on hold for want of time, or clear the file without exercising due diligence. No thought is given to a situation where adoptive parents may, at some point later, discover that the child they adopted had been kidnapped or procured illegally. Knowingly or unknowingly they will have contributed to the commission of a crime.

It can be devastating for both, the adoptive parents and the adopted child, and more so if the child’s biological parents are still hoping to get reunited. Such adoption will not stand the test of law either.

We have no data to tell us how much time is taken at different stages in the adoption process in order to figure out what exactly needs to be corrected. Quick fix solutions based on gut and intuition, or some horrifying tales instead of evidence – cannot be the way to treat children if we claim to be a loving and caring nation.

Image source: Infographics made by Shalabha Sarath with information from author Bharti Ali, and header image a still from the film Lion

Source: https://www.womensweb.in/