Menu

MenuStop Plan to Lower Marriage Age to 16

Belkis, 15 years old, holds her one-year-old son in her mother’s house which she returned to after the husband she was married to at age 13 abandoned her. She fears her family’s home will be washed away by river erosion by the end of the year.

© 2015 Omi for Human Rights Watch

(Dhaka) – The Bangladesh government is yet to take sufficient steps to end child marriage, in spite of promises to do so, Human Rights Watch said in a new report released today. Instead, in steps in the wrong direction, after her July 2014 pledge to end child marriage by 2041, Bangladesh Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina attempted to lower the age of marriage for girls from 18 to 16 years old, raising serious doubts about her commitment.

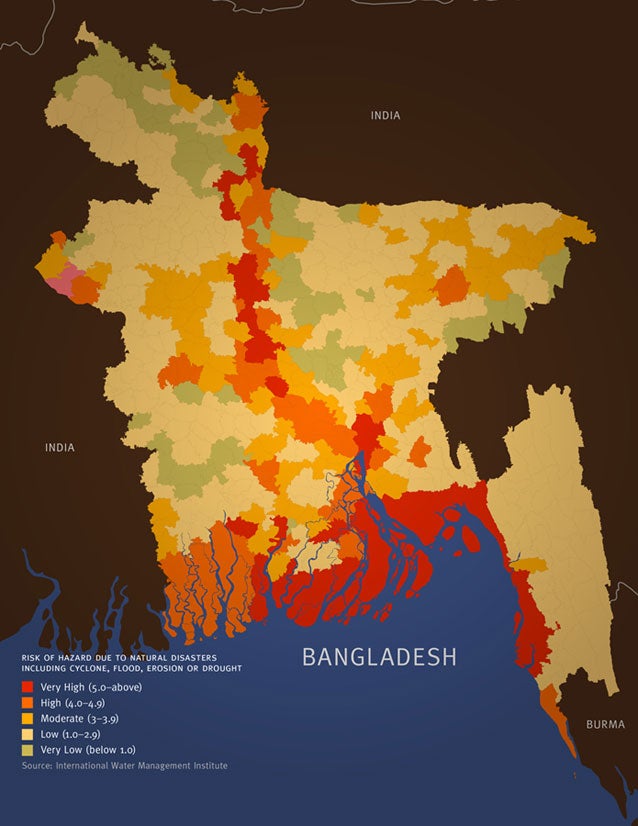

Bangladesh has the highest rate of child marriage of girls under the age of 15 in the world, with 29 percent of girls in Bangladesh married before age 15, according to a UNICEF study. Two percent of girls in Bangladesh are married before age 11. Successive inaction by the central government and complicity by local officials allows child marriage, including of very young girls, to continue unchecked, while Bangladesh’s high vulnerability to natural disasters puts more girls at risk as their families are pushed into the poverty that helps drive decisions to have girls married.

“Child marriage is an epidemic in Bangladesh, and only worsens with natural disasters,” saidHeather Barr, senior researcher on women’s rights. “The Bangladesh government has said some of the right things, but its proposal to lower the age of marriage for girls sends the opposite message. The government should act before another generation of girls is lost."

The 134-page report, “Marry Before Your House is Swept Away: Child Marriage in Bangladesh,” is based on more than a hundred interviews conducted across the country, most of them with married girls, some as young as age 10. It documents the factors driving child marriage in Bangladesh – including poverty, natural disasters, lack of access to education, social pressure, harassment, and dowry. Human Rights Watch also details the damage that child marriage does to the lives of girls and their families in Bangladesh, including the discontinuation of secondary education, serious health consequences including death as a result of early pregnancy, abandonment, and domestic violence from spouses and in-laws.

Child marriage has been illegal in Bangladesh since 1929, and the minimum age of marriage has been set at 18 for women and 21 for men since the 1980s. In spite of this, Bangladesh has the fourth-highest rate in the world of child marriage before age 18, after Niger, the Central African Republic, and Chad. Sixty-five percent of girls in Bangladesh marry before age 18.

The government’s failure to enforce the existing law against child marriage and address the factors that contribute to it means that child marriage is a frequent coping mechanism for poor families:

Another finding of the report is the role natural disasters play in child marriage. Bangladesh is among the countries in the world most affected by natural disasters and climate change; many families are pushed by disasters into deepening poverty, which increases the risk that their daughters will be married as children. Families described feeling under pressure to arrange marriages quickly for their young daughters in the wake of a disaster, or in the anticipation of one. This was particularly common among families who faced losing their home and land through the gradual destruction caused by river erosion.

The Bangladesh government is failing to take effective action against child marriage. In 2014, at the international “Girl Summit” held in London, United Kingdom, Bangladesh’s prime minister vowed to end child marriage. She outlined a series of steps to do so, including reform of the law and development of a national plan of action by the end of 2014. Neither of these steps have been achieved. Worse yet, the Bangladesh government has taken a step in the wrong direction by proposing to lower the minimum age of marriage for girls from 18 to 16 years old.

Many local government officials also fail girls at risk. Awareness is growing that marriage of girls under age 18 is illegal under Bangladeshi law. But this awareness is fatally undermined by widespread complicity by local government officials in facilitating child marriages. Interviewees consistently described local government officials issuing forged birth certificates showing girls’ ages as over 18, in return for bribes of as little as US$1.30. Even when marriages are prevented by local officials, as they sometimes are, families find it easy to hold the marriage in a different jurisdiction.

“The Bangladesh government should follow through vigorously and promptly on the public commitments Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina made to end child marriage,” Barr said. “The first step should be to back away immediately from the proposal to lower the age of marriage for girls to 16.”

In some other ways, Bangladesh has been cited as a development success story, including in the area of women’s rights. The United Nations cited Bangladesh’s “impressive” poverty reduction from 56.7 percent in 1991-1992 to 31.5 percent in 2010. Bangladesh has achieved gender parity in primary and secondary school enrollment. Maternal mortality declined by 40 percent between 2001 and 2010. Bangladesh’s success in achieving some development goals begs the question of why the country’s rate of child marriage remains so high, among the worst in the world.

As a party to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, and the Convention on the Rights of the Child, Bangladesh has international obligations to protect the rights of girls and women, including the right to be free from discrimination, to the highest attainable standard of health, to education, to free and full consent to marriage, to choose one’s spouse, and to be free from physical, mental, and sexual violence. Human Rights Watch found that child marriage in Bangladesh can result in the inadequate fulfilment and protection of these rights.

Human Rights Watch’s village-level research documents a failure to enforce the law against child marriage and crucial gaps in health, education, and social support programs that should be doing more to assist girls at risk of child marriage. The government has taken important strides in facilitating access to education by banning primary level school fees. But other costs associated with attending school mean that education, especially at the secondary level, remains out of reach for too many children, and for girls in Bangladesh the consequence can often be child marriage. Government agencies providing assistance to families in poverty or affected by disasters should be better harnessed to prevent child marriage. Access to information about reproductive health and to contraceptive supplies is out of reach for many of the girls who need it most. Girls facing violence and abuse we interviewed often had nowhere to turn for help. Bangladesh’s law on child marriage needs to be reformed, but even more importantly, it needs to be fully enforced.

“The Bangladesh government’s inaction on child marriage is causing devastating harm to one of the country’s greatest assets – its young women,” said Barr. “The government—and its donors—should do more to keep girls in school, assist girls at risk of child marriage, fight sexual harassment, and provide access to reproductive health information and contraceptive supplies. Most importantly, the government should enforce its own law against child marriage.”

Selected Testimony

“I don’t have enough money to feed my daughters – that’s how I decide when I should marry them.” –Fatima A., mother of five.

“Whatever land my father had and the house he had went under the water in the river erosion and that’s why my parents decided to get me married.” –Sultana M., who married at age 14 and is now 16 years old and 7 months pregnant.

“I got married because I quit school.” –Mariam A., who married at age 15. She left school after class 5 because going on to class 6 would have involved higher costs and a longer walk of 3.5 kilometers each way.

“Elders [male community leaders] in the area might say your daughter is getting old,” is Rekha H.’s explanation for why both her older and younger sisters were married at age 11, and Rekha herself married at age 12. “No one said anything, but [my parents] were afraid, so before anyone could they got us married.”

“Now she is pretty and young and we can give her away for free. If you bring the police we will have more problems when she gets older.” –Ruhana M.’s older brother, arguing for why Ruhana should marry at age 12, after her uncle threatened to prevent the marriage. The marriage went forward.

Rabiya A. married when she was 13 and her husband was 30. “My in-laws said, ‘If you want to study you can,’ but as soon as I was married they said, ‘It’s not possible,’” Rabiya said. Rabiya is now 14 and said her in-laws and husband are disappointed that she is not pregnant yet.

“My in-laws didn’t really want babies, but I didn’t understand how to take medicines to not have a child. I was very young, so I just got pregnant.” –Lakshmi S., who married at age 12 and now, at age 18, is the mother of a 6-year-old son and an infant daughter.

“[H]e forcibly entered me and I would cry so much that everything would get wet from my tears. It was so difficult, so painful. The first time, the next day I couldn’t even move and they took me and gave me a bath.” –Rashida L., who married when she was 10 or 11.

“When the Kazi [Muslim marriage registrar] saw that my daughter’s birth certificate said that she was 14, he refused to do the marriage,” said Farhana B. “He took it to the [local government] chairman and got it changed and then did the marriage.” The chairman charged the family 100 taka [$1.30] to change the birth certificate.

“This is a place affected by river erosion,” Azima B.’s parents told her, explaining why she had to marry at age 13. “If the river takes our house it will be hard for you to get married so it’s better if you get married now.”