Menu

Menu

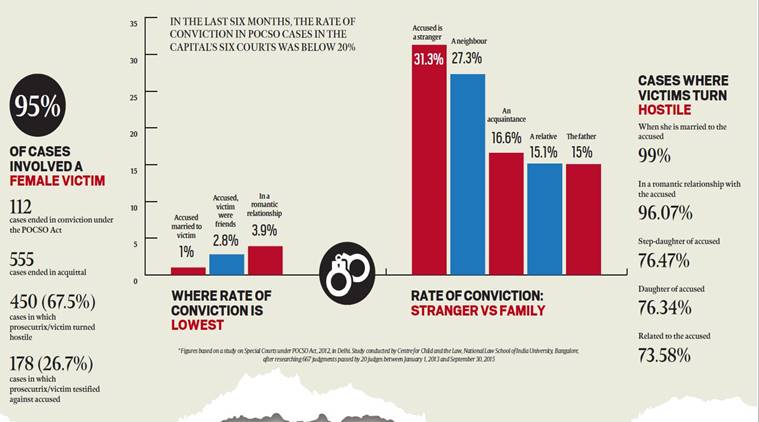

Hearing a PIL last year, the Delhi High Court was told that only 18.49 per cent of people accused of child sexual abuse under the POCSO (Protection of Children from Sexual Offences) Act were found guilty by courts in the capital in the first half of 2016. The Delhi State Legal Services Authority (DSLSA), which informed the court of this figure, said the conviction rate “leaves an unsavoury image of the way the criminal justice system is being administered in Delhi, and creates alarm in the mind of the general public that child victims of rape and sexual offences are not getting justice”.

But 2016 wasn’t a standalone case. In 2014, the conviction rate in POCSO cases was 16.33 per cent, while 2015 saw a conviction rate of 19.65 per cent. An analysis of POCSO judgments of the six courts in the capital — Saket, Dwarka, Rohini, Patiala House, Tis Hazari and Karkardooma — in the last six months found that the conviction rate was below 20 per cent.

In a majority of cases that ended in acquittals, the judgments noted that the “prosecution had failed to prove its case”. To understand why, The Indian Express spoke to a spectrum of stakeholders, including POCSO prosecutors who come under the Delhi government and are tasked with bringing the guilty to book.

A hostile problem

For a 50-year-old additional public prosecutor at Tis Hazari court, the day starts at 10 am. On an average, he deals with 12-15 POCSO cases a day. On Friday, most of his cases were at the evidence stage — when he is supposed to call witnesses to testify. In one particular case, the alleged victim had turned hostile. “It is a problem in most cases. While recording their statement under CrPC Section 164, they give one version, but during their testimony before court, it changes,” he said.

In fact, in most acquittals, it was found that the prosecutrix (the alleged victim) — considered the ‘sterling witness’ in court parlance — had turned hostile. Simply put, the testimony of the alleged victim was found to contradict the legal position of the prosecution.

A report by the National Law School Bangalore, which analysed 667 judgments between 2013 and 2015, shed light on this phenomenon. It stated that alleged victims turned hostile in “67.5% cases, and testified against the accused in only 26.7% cases”.

Experts The Indian Express spoke to explained that once a POCSO case is filed, the long-winded proceedings give the accused ample time to try and pressure the victims or their families to backtrack on their complaints. The situation is even more complicated when the accused is a family member.

In such cases, experts said, the conviction rate drops even further.

At the prosecution branch of the Tis Hazari court, the prosecutor expressed concern over how children between ages 15-18 turn hostile. “Since the procedure is long-drawn, victims are easily won over or pressured by the accused,” he said. “A majority of these victims are from the lower economic strata, so they are more vulnerable to pressure.”

He added that it is toughest to get a conviction in cases where the accused is a family member. “In the immediate aftermath of such crimes, the victim continues to live in the same house as the accused — be it a father or a relative — and is also emotionally attached to them. In many cases, the mother convinces the child to let it go.”

In a 2016 case from Swaroop Nagar, for instance, the accused was charged with allegedly trying to rape his step-daughter. It was alleged that the accused, who was drunk at the time, tore the girl’s clothes and stopped only when her mother intervened.

But in her deposition in the Rohini court, the girl said: “In 2016, the accused started drinking heavily and used to quarrel with my mother about trivial issues, and beat me, my mother and sisters. Fed up with his behaviour, they wanted to teach him a lesson and lodged a complaint.”

Pronouncing the judgment, special judge Seema Mani said, “There is nothing that survives in the prosecution’s case — which falls flat on its face — failing to bring home the guilt of the accused.”

Mind the gap

In the face of such challenges, some of the respondents to the National Law School study, which included police and public prosecutors, suggested that children “need to be separated from the family in cases where the alleged perpetrator is a family member”. They also suggested keeping children in a shelter home until the trial.

But others who participated in the study opposed the idea, saying that recording of evidence can be delayed by three-four months and the child cannot be “detained” until then. “Such a decision should be taken on a case-to-case basis, keeping in mind the principle of best interest. Besides, considering the pathetic condition of children’s homes, children would prefer to return to their homes,” the study said, quoting some respondents.

Wasi-ur-Rehman — who worked in Saket court as a POCSO public prosecutor and now works at Karkardooma — said the other challenge is that perjury rules don’t apply to children, which makes them open to exploitation. “A minor, under the POCSO Act, is safeguarded from penal action provisions in case of perjury. So there is no deterrence,” Rehman said.

A Delhi court specifically mentioned this in August, in the case of a 15-year-old girl who had alleged rape. However, during court proceedings, she deposed in favour of the accused, saying she had been pressured into filing a complaint. While acquitting the accused, the court had noted, “No doubt the complaint, on the basis of which the FIR has been registered, is in the own handwriting of the victim, and (she has) also given statement under Section 164 of the CrPC against the accused, from which she has now resiled. But she cannot be prosecuted for any perjury due to Section 22(2) of the POCSO Act.”

In another case, a minor girl had filed a complaint in Geeta Colony police station alleging that an auto driver forcibly made her sit in his vehicle, put his hands inside her clothes and sexually assaulted her.

But during the prosecution examination, she turned hostile and refused to identify the accused. “… from the statement of the victim, it is revealed that she was tutored prior to giving the statement under Section 164 of the CrPC and was directed to give a particular and specific version by an NGO official,” Additional Sessions Judge Ashwini Kumar Sarpal said.

He added that in such circumstances, when the main and material witnesses have turned hostile, recording of evidence of the remaining official witnesses is dispensed with. “Hence, the accused is acquitted,” the judge said. A senior police officer highlighted another facet of the problem: “Under POCSO, consent does not matter. Some of the cases are romantic in nature, so the statement of the victim is bound to be in favour of the accused.”

A tedious process

The POCSO Act was enacted in 2012 to protect children from sexual assault, harassment and pornography. The Act also mandated setting up of special courts, where such cases can be tried expeditiously. Every stage of the judicial process was intended to be child-friendly — something that hasn’t exactly happened, experts said.

While most courts have a ‘vulnerable witness deposition room’, from where victims interact with judges or prosecutors, the process is lengthy and tedious.

A prosecutor explained, “First, I convey my question to the judge, who then asks a question over microphone to the victim sitting in a different room. Sometimes, a child support person conveys the question to the victim, who either answers directly or whispers into the person’s ear if they are scared.”

“There needs to be clear coordination between victims and prosecutors. We have minimum facilities and are not equipped to speak to victims. There is no separate room for their visit. If a prosecutor gets enough time to take the victims into confidence, the process can be shortened,” he added.

Another prosecutor explained that sometimes, defence lawyers play “tricks” to “manipulate” victims. “Sometimes, when a prosecutor calls the alleged victim to depose, the defence does not cross-examine her at the time. Instead, they use provisions of CrPC section 311 to re-examine the victim at a later stage, when the accused, or his family members, has already coerced her,” he said.

The Delhi Commission for Women (DCW), which offers counselling as well as legal help to victims, often plays a crucial role in POCSO cases.

DCW chief Swati Maliwal agreed that more facilities and resources are needed for the prosecution department. She added that while there ought to be special courts to exclusively look after POCSO cases, many courts hear other cases as well. “Therefore, it takes a lot of time. Plus, police investigation needs to be efficient. All these things increase the gaps, and victims and their families slowly start losing faith in the system,” she said.

On the issue of delay in getting forensic reports, Maliwal added: “In October 2015, as many as 7,500 forensic reports were pending. Of this, 1,800 were putrefied. We issued notice to various stakeholders. As of now, pendency rate has reduced to 50 per cent.”

A judge’s take

A Principal judge at a family court in Delhi, who has dealt with POCSO cases and used to be a member secretary with the Delhi State Legal Services Authority, explains the reasons behind the low conviction rate, and the problems around it:

“There are many Romeo and Juliet-like love story cases, where there is experimentation but no exploitation. It is simple love and infatuation. What is the point of conviction in such cases?

“Regarding incest cases, the entire family gets involved to stop the victim from deposing against the accused. In such cases, police should handle it delicately and file a chargesheet as soon as possible. There is also a problem of where the victims should stay. Our children’s homes are in a bad shape — just like a detention centre. It is not a place where they can get a good education, environment and hygiene.

“In Delhi, every district has one POCSO court. For instance, if the northwest district has 1,100 cases, it is nearly impossible for the judge to dispose them quickly — deposition of the victim alone takes three-four hours. The rationalisation of work should be considered by the High Court, which should set a benchmark that judges deal with only, let’s say, 250-300 cases. There should be a committee to look for the most vulnerable — places from where most cases are coming. Accordingly, there should be awareness, education, and policing. Many POCSO cases are from

JJ clusters and resettlement colonies, so there is a need for multi-pronged strategies. “For mentally disabled victims, the value of forensics increases — reports of which are often delayed. Such children are a minority, but DNA testing is significant in deciding the case. Moreover, the method used for DNA testing is outdated.”